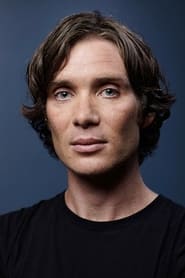

When it comes to minimalism in filmmaking, there’s deftly deliberate understatement, which can be a decidedly valuable asset, and then there’s cryptic obfuscation, which frequently leaves viewers scratching their heads. And, when it comes to this fourth feature outing from director Tim Mielants, the line between the two is undeniably and confusingly razor thin, a tale that’s so exceedingly nuanced and purposely restrained that one often wonders exactly what it’s trying to say. Set in 1985, the film tells the story of Bill Furlong (Cillian Murphy), a hard-working Irish coal merchant struggling to make ends meet for his wife (Eileen Walsh) and five daughters. As a soft-spoken, kind-hearted soul, he readily helps others in need, a compassionate streak he developed in childhood when his younger self (Louis Kirwan) and unwed mother, Sara (Agnes O’Casey), were graciously taken in by a wealthy benefactor (Michelle Fairley) when they were summarily ostracized by Sara’s family, a story thread depicted in a series of flashbacks. That quality comes to define Bill’s nature, resurfacing recurringly years later. But its impact becomes most apparent when he makes a coal delivery to the local convent, where he witnesses the infliction of unduly cruel treatment on a pregnant teen (Zara Devlin), one of many such young women who reside at the facility while waiting to give birth. As it turns out, the convent is part of Ireland’s infamous network of Magdalene laundries, facilities run by the Catholic Church where young unwed mothers-to-be were essentially treated like slave labor in exchange for room and board during their pregnancies, a program that operated largely unknown on the Emerald Isle for more than 75 years. And, when Bill meets with the convent’s cold-hearted Mother Superior, Sr. Mary (Emily Watson), about a subsequent incident, he witnesses just how troubling the conditions can get, He’s torn how to respond, too, given the stranglehold that the Church and the convent have over the lives of virtually everyone in the surrounding community. Indeed, what is he to do? From the foregoing summary, this would seem to make for an intriguing movie premise, but virtually every aspect of the film is so willfully downplayed that it barely scratches the surface of this shocking story, one that rocked Ireland and the Church worldwide when it ubiquitously surfaced in the mainstream media. To make matters worse, the film lacks any significant emotional depth, never doing much to draw audiences into the story or the lives of its characters. In large part that’s attributable to the undercooked screenplay and its woeful character development, which is so subdued that little stands out about who these individuals are, with nearly all of the cast (except for Watson, who turns in a superb portrayal) delivering performances that could have easily been phoned in. While it’s certainly commendable that the filmmaker resisted the temptation to sensationalize this story, the finished product nevertheless fails to deliver the goods. (Indeed, for a better, more engaging, more telling treatment of this subject, watch the excellent fact-based drama “Philomena” (2013) instead.) It should go without saying that the victims of this unforgivable fiasco truly deserve better than what’s depicted in this release, and it’s regrettable that they don’t get it, no matter how noble the intentions of this picture’s creators might have been.